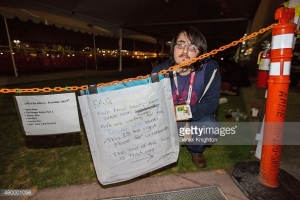

Jason Kaus at Comic-con 2015. He was first in line for Hall H and visited by the Doctor.

Kennedy’s Inaugural Address was Fifty Years Ago Today

•January 20, 2011 • Leave a CommentFifty years ago today John F. Kennedy gave the greatest speech of my lifetime.

There were televisions in each classroom at El Rodeo Elementary School and we all watched the inauguration, the first one we had ever seen. Many people who I have met say the same thing happened at their schools. I have often wondered what caused school administrators to set this up as it had never happened before.

JFK was young even to me, and I was 12. As I heard Peggy Noonan say on the radio yesterday, we did not know that a president could be our parents’ age rather than our grandparents’ age or that he did not have to have grey hair.

The day seemed historic even at the time, from Robert Frost’s inability in the glare to see the text of the poem he had written for the occasion to the soaring rhetoric and almost comical dress clothes. The speech apparently was largely written by Theodore Sorenson, who died just last October. I memorized it for our 8th grade speech contest and I can still do a pretty good job today, somewhat to the annoyance of my family.

There are many critiques of Kennedy’s short period in office, but that day created a spirit of hope and aspiration that those of us who saw it will never forget.

It is worth watching. Only 14 minutes long.

Borrowers Questions Good Enough to Require Response From Lender Under RESPA; Summary Judgment Overturned by Seventh Circuit

•January 17, 2011 • Leave a CommentThe Seventh Circuit has reversed a summary judgment that GMAC had obtained in District Court against a complaint alleging violations of RESPA section 12 U.S.C. 2605(e), which requires a lender to investigate and respond when a borrower makes a “Qualified Written Request” (“QWR”) asking for information or reporting an error in their account. (Catalan v. GMAC Mortgage Corp. __ F 3d __ (7th Cir. January 10, 2011))

The borrowers in this case tell a sad story of mistakes and obtuse responses, compounded by an assignment of the loan to GMAC in the middle of the problems. Borrowers purchased a home in June 2003 and obtained a 5.5% 30 year fixed loan from RBC Mortgage Company, which would set most people on a happy course. However, unknown to the borrowers, RBC miscoded the loan so that the first payment was due in July, rather than in August, which was the correct date. This set off a daisy chain of errors, returned and mis-credited checks and miscommunications.

While the home was in a slow-motion foreclosure process, with several payments being made, some of which were correctly credited, RBC assigned the loan to GMAC. GMAC continued to send incorrect communications, including demands for payment and reports of renewed assignment for foreclosure and alleged delinquency reports to credit agencies. In 2005, through the intercession of HUD, the financial issues were resolved, with the borrowers not paying any fees or penalties.

Borrowers sued under 12 U.S.C. 2605(e), which requires a loan servicer to acknowledge and respond to a QWR that requests information or states reasons for the borrower’s belief that the account is in error. The QWR must include the name and account of the borrower or must enable the servicer to identify them.

Within 60 days after receiving a QWR, a loan servicer must (1) make appropriate corrections to the borrower’s account and notify the borrower in writing of the corrections; (2) investigate the borrower’s account and provide the borrower with a written clarification as to why the servicer believes the borrower’s account to be correct; or (3) investigate the borrower’s account and either provide the requested information or provide an explanation as to why the requested information is unavailable. The servicer must provide a name and telephone number of a person who can assist the borrower.

The borrowers contended that five written communications they had sent were QWRs. The Court of Appeal agreed as to two, one of which was relayed through HUD, finding that they adequately reported an error in the account that triggered the response requirement. The other communications merely stated requests for handling of the loan, but did not adequately request information or report errors. The District Court had found that GMAC qualified for a safe harbor based on its eventual correction of the account records, but the appellate court found that GMAC did not properly “notif[y] the person concerned of the error” and therefore did not qualify for the safe harbor.

The Court of Appeal also

•reinstated the borrower’s breach of contract cause of action. The District Court had agreed with GMAC that the borrowers themselves had first breached the contract by failing to make payment, although GMAC had refused to apply the checks that the borrowers had sent. The appellate court felt that a reasonable jury could conclude that borrowers had done their best.

•Agreed that no tort could be stated. Under the economic loss doctrine, there can be no tort recovery for economic losses based on failure to perform contractual obligations.

•Found that borrowers had adequately stated recoverable damages based on rejections of several loan applications, including three loans at LaSalle Bank. (“We are not quite done yet,” the Court states on page 36 of its opinion) Although a LaSalle loan officer testified that the loan applications would have been rejected regardless of the issues in this case, borrowers were permitted to introduce a statement by a LaSalle loan officer told her that borrowers’ loan applications would not be approved until their foreclosure was removed. GMAC contended that this was “classic” hearsay, but the Court found that the statement either was not hearsay because it was a statement of the bank’s intentions or was admissible under the state of mind exception.

What Happens at JAMS, Stays at JAMS

•January 15, 2011 • Leave a CommentIn an opinion that is based on a literal reading of California’s mediation confidentiality statute (Evidence Code §§1115 et seq.), the State Supreme Court unanimously held in Cassel v. Superior Court (1-13-2011) __ Cal 4th __ that a client cannot use his attorney’s bad advice during a mediation as evidence in a subsequent suit for malpractice.

The mediation statute means what it says that “[a]ll communications, negotiations, or settlement discussions by and between participants in the course of a mediation . . . shall remain confidential.” “Participants” means everyone, lawyers included. Nothing in the statute, the Court holds, provides that communications must involve the actual parties or the other side of the dispute.

The alleged facts present a reasonably compelling case for disclosure. In a mediation of a business dispute, Michael Cassel, a fashion clothing distributor, told his attorneys that he would not settle for less than $2 million. However, he alleges, his attorneys improperly induced him to settle for only $1.25 million. While not on a par with the sleep deprivation and other persuasive measures allegedly used on terrorist suspects, the following description from the opinion sets out the measures, including following Cassel into the bathroom, that he alleges were sufficient to cause him to do something he did not want to do:

“Though he felt increasingly tired, hungry, and ill, his attorneys insisted he remain until the mediation was concluded, and they pressed him to accept the offer, telling him he was “greedy” to insist on more. At one point, petitioner left to eat, rest, and consult with his family, but [one of the attorneys] called and told petitioner he had to come back. Upon his return, his lawyers continued to harass and coerce him to accept a $1.25 million settlement. They threatened to abandon him at the imminently pending trial, misrepresented certain significant terms of the proposed settlement, and falsely assured him they could and would negotiate a side deal that would recoup deficits in the . . . settlement itself. They also falsely said they would waive or discount a large portion of his $188,000 legal bill if he accepted [the[ offer. They even insisted on accompanying him to the bathroom, where they continued to “hammer” him to settle. Finally, at midnight, after 14 hours of mediation, when he was exhausted and unable to think clearly, the attorneys presented a written draft settlement agreement and evaded his questions about its 6 complicated terms. Seeing no way to find new counsel before trial, and believing he had no other choice, he signed the agreement.”

The opinion, which overrules a contrary decision in the case by the Court of Appeal, but is consistent with an intervening U.S. District Court case authored by Magistrate Judge Elizabeth Laporte (Benesch v. Green (N.D.Cal. 2009) 2009 WL 4885215), spends most of its thirty two typed pages parsing the language of the statute to fend off various constructions offered by Cassel’s attorneys to allow admission of private communications between a client and his attorney. Although the attorney-client privilege has an exception for litigation between attorney and client, the Court finds no basis to adopt an analogous exception for mediation confidentiality. The attorney is a “participant,” who is as entitled to confidentiality as the client.

The Court cites its past decisions that established a strong mediation privilege without court-made exceptions, unless a parties due process rights were threatened. In previous cases, the Court has refused to allow mediators to report that parties had not participated in good faith (Foxgate Homeowners’ Assn. v. Bramalea California, Inc. (2001) 26 Cal.4th 1.), refused to allow a “good cause” exception for writings prepared for a mediation (Rojas v. Superior Court (2004) 33 Cal.4th 407) and required that a settlement agreement reached at a mediation contain specific words that it was intended to be binding and enforceable before it can be used in an enforcement proceeding (Fair v. Bakhtiari (2006) 40 Cal.4th 189. Although there are exceptions provided in the statute when all of the participants agree to waive confidentiality, judicial principles such as equitable estoppel and implied waiver do not apply to mediation confidentiality (Simmons v. Ghaderi (2008) 44 Cal.4th 570).

In all of these cases, as here, the Court read the statute quite literally. The only recognized exceptions are waiver by all parties and to avoid a due process violation. The due process exception, does not apply when the evidence is needed in civil litigation. The Court distinguishes Rinaker v. Superior Court (1998) 62 Cal.App.4th 155, where mediation confidentiality gave way to juvenile court criminal defendants’ right to confront witnesses and present exculpatory evidence.

What policy, other than protection of attorneys, could possibly justify this result? Toward the end, the Court offers three possibilities. It would not have been unreasonable for the legislature to believe that (1) total privilege “gives maximum assurance that disclosure of an ancillary mediation related communication will not, perhaps inadvertently, breach the confidentiality of the mediation proceedings themselves, to the damage of one of the mediation disputants,” (2) that “protecting attorney-client conversations in this context facilitates the use of mediation as a means of dispute resolution by allowing frank discussions between a mediation disputant and the disputant’s counsel about the strengths and weaknesses of the case, the progress of negotiations, and the terms of a fair settlement, without concern that the things said by either the client or the lawyers will become the subjects of later litigation against either.” or (3) that “it would not be fair to allow a client to support a malpractice claim with excerpts from private discussions with counsel concerning the mediation, while barring the attorneys from placing such discussions in context by citing communications within the mediation proceedings themselves.”

The legislature, the Court counsels, is free to amend the law if it believes a change is warranted or that it has been misunderstood. Until then, clients are well advised to be well rested and bring granola bars and water to any mediation.

THIS ENTRY IS CROSS-POSTED FROM THE COOPER, WHITE & COOPER LLP WEBSITE AT http://www.cwclaw.com.

Giants Telecast Throwback in Standard Definition

•August 11, 2010 • Leave a CommentCalifornia Supreme Court Restores Sanity to Summary Judgment Evidence Objections

•August 7, 2010 • Leave a CommentThursday, August 05, 2010

Until today, one of the most dysfunctional areas of litigation was the apparent requirement that a party who made written objections to evidence offered in a summary judgment proceeding had to force the trial judge to rule on the motions or was deemed to have waived the objection. Aside from the questionable statutory basis for this rule, as a practical matter, the result often was a tense confrontation between the attorney, who was forced to press for a ruling in order not to waive the multitude of objections that had been made on paper, and the trial judge, who did not want to spend the time or effort deciding what often was an overwhelming number of inconsequential evidentiary issues.

In Reid v. Google Inc. (August 5, 2010) __ Cal.4th __ (Reid), common sense prevailed and the California Supreme Court ruled that (1) objections need only be made in writing, not also at the hearing, and (2) objections are deemed to be overruled if no actual ruling is made, rather than waived. The key distinction between having an objection overruled and having waived an objection is that an objection that has been overruled is preserved for appeal.

The genesis of the problem was California Civil Code §437c, subd. (b)(5), which states that “[e]videntiary objections not made at the hearing shall be deemed waived.” and Section 437c, subd. (d), which requires that any objections based on failure to establish a foundation “shall be made at the hearing or shall be deemed waived.” As is recounted in Reid, two competing and confounding lines of cases dealing with these requirements caused uncertainty, annoyance and unjust results.

The first line of cases, based on the reasoning of Biljac Associates v. First Interstate Bank(1990) 218 Cal.App.3d 1410, 1419 (Biljac), excused the trial court judge from having to make specific rulings on objections. In Biljac, the plaintiff sought trial court rulings on the voluminous objections he had filed, but the judge refused, calling that “a horrendous, incredibly time-consuming task” that “would serve very little useful purpose.” On appeal, the plaintiff argued that this was reversible error, but the Court of Appeal held that express rulings were not needed because the objections would be renewed de novo on appeal. Under Biljac, it was enough that the judge said the ruling was based only on competent and admissible evidence.

However, in two cases that ignored Biljac, the Supreme Court held that if an attorney did not actually obtain specific rulings on objections, the objections were waived and not preserved for appeal. Ann M. v. Pacific Plaza Shopping Center(1993) 6 Cal.4th 666 (Ann M.); Sharon P. v. Arman, Ltd.(1999) 21 Cal.4th 1181, 1186-1187, footnote 1 (Sharon P.).) Under this theory, ostensibly based on a reading of the summary judgment statute §437c, if there was no specific ruling on meritorious objections, the appeal would be decided as if the evidence had been admissible.

Chaos ensued, as many courts of appeal disapproved Biljac, some finding waiver, some ruling on the objections and some sending the case back to the trial court to make rulings. A particularly preposterous development, referred to in Reid as the “stamp and scream” rule, required attorneys to avoid waiver by asking for a ruling with sufficient vigor at the hearing, even if no ruling was obtained as a result. See e.g.City of Long Beach v. Farmers & Merchants Bank(2000) 81 Cal.App.4th 780, 783-785.

Reid, in a unanimous decision authored by Justice Chin, settles this confusion based on a combination of the history of the summary judgment statute and common sense. The first problem is the requirement that objections be made “at the hearing.” Although the statute allows objections to either be in writing five days before the hearing or orally at the hearing, appellate courts were divided on whether written objections were made “at the hearing” or if they had to be orally reiterated. Reid reasons that at a hearing, the court considers memoranda, arguments and evidentiary objections, so, “written evidentiary objections made before the hearing, as well as oral objections made at the hearing are deemed made ―at the hearing under section 437c, subdivisions (b)(5) and (d), so that either method of objection avoids waiver.” (Slip Op. at 23.)

Next, Reid requires the trial court to rule on the motions, but holds that if no ruling is obtained, the objections are deemed to be overruled. Contrary to Ann M. and Sharon P., the objections are preserved for appeal and are not waived.

Stating that it has “become common practice for litigants to flood the trial courts with inconsequential written evidentiary objections, without focusing on those that are critical,” the court encouraged litigants “to raise only meritorious objections to items of evidence that are legitimately in dispute and pertinent to the disposition of the summary judgment motion. In other words, litigants should focus on the objections that really count. Otherwise, they may face informal reprimands or formal sanctions for engaging in abusive practices.” (Slip Op. at 24.)

Surely, this is the ruling for which all litigators had hoped. Summary judgment hearings had become needlessly tedious and were not focused on the key issues. Moreover, at the same time an attorney was trying to persuade a judge on the merits, the attorney also had to annoy the judge by pressing for evidentiary rulings. Any summary judgment motion contains many more points than can be discussed at a hearing. Now one can focus on the key points without the danger of waiving the ones that are only in the papers.

Originally posted on the Cooper, White & Cooper LLP web site.

California Supreme Court

Welcome Back Mark McGwire, Savior of Baseball

•January 17, 2010 • Leave a Comment“I wish I had never touched steroids. It was foolish and it was a mistake. I truly apologize. Looking back, I wish I had never played during the steroid era.”

Now we officially know that Mark McGwire used Performance Enhancing Drugs (“PEDs”)

What we don’t know with any assurance is who did not use PEDs.

So when Tim Brown of Yahoo attacks Mark McGwire by saying that McGwire “was the steroid era” and that McGwire “wasted our time,” Brown is talking nonsense. Yes, all players did not use steroids, but many, maybe most, did. What made Mark McGwire different was that he was the second best juicer at hitting home runs.

Also, he saved baseball in 1998. Remember? If he hadn’t, Brown might be writing about a sport with an equivalent stature to hockey.

McGwire is correct to regret being a player in the steroid era. Had there not been a steroid era, McGwire would be in the Hall of Fame already.

The evidence that “everyone” used PEDs is strong. The Mitchell Report identified 89 players who allegedly used. But, we know this was a sampling, not anything near a complete list. Aside from a handful of random people who spontaneously confessed or were accidentally detected, the Mitchell Report only includes those in webs connected to five providers: BALCO, former Met batboy and clubhouse employee Kirk Radomski, former Yankee strength coach Brian McNamee, and two rejuvenation clinics in the South. Fifty two were associated with Radomski, who was required to talk to Mitchell as part of his sentence for money laundering and illegal drug distribution.

Only a fool would believe that all, or even most of the PEDs in MLB came from these five sources. These providers are just the ones who were busted and forced to squeal. You have to believe that there were providers in all major league cities. Think Houston or St Louis. Or the Bash Brothers. McGwire’s use was apparently connected to widespread availability connected to gyms, as presumably was the case with many others. Sammy Sosa, to pick a random name, has not been connected with any of these sources.

In 2002, the Major League Players Association agreed to testing of all players to see if there was a problem. 104 players tested positive, admittedly a group with some overlap to those identified in the Mitchell report. The results were supposed to be kept secret, but some, like David Ortiz and A-Rod, have leaked out since the federal government obtained a copy of the list.

But wait, there’s more. Testing procedures have improved since these 2002 tests. Barry Bonds apparently was not on the original list, but when his sample was retested in 2004 at UCLA, it came back positive. It is unknown how many of the “clean” samples in 2002 would be dirty if retested today. Probably quite a few.

Maybe everyone did not use steroids, but it may be easier to count those who did not. Some others who claim not to have used did their bit by being active in the player’s union’s resistance to effective testing or significant sanctions. All concerned share the blame for enjoying the feats rather than doing anything about the drugs. It is patently unfair to put the onus on McGwire.

He should be back in baseball, as he now is, and because he was an elite player, he should be in the Hall of Fame. His “confession,” while inartful, has far more truth than A-Rod’s or Ortiz’s. Time to accept him and move on.

Who knew?

1990

1998

Fighting Sotomayor, Republicans Falsely Advance Fire Fighter Ricci as the White Man’s Rosa Parks

•July 13, 2009 • 3 CommentsWhen the Senate hearings on the nomination of Judge Sondra Sotomayor for the U.S. Supreme Court start Monday, one focus will be the case of Ricci v. New Haven. In Ricci, Judge Sotomayor concurred in a Court of Appeal opinion that affirmed a lower court decision that the New Haven Civil Service Board (“CSB”) was entitled to hold a new exam when it determined that the old exam measured skin color more than it measured qualifications to be a lieutenant or captain in the New Haven Fire Department.

The Court of Appeal decision is not unsympathetic to Ricci. It just holds that the CSB had the discretion to hold a new test in light of the clear disparate impact and the evidence that the test was not sufficiently job related to provide justification.

We affirm, for the reasons stated in the thorough, thoughtful, and well-reasoned opinion of the court below. Ricci v. DeStefano, 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 73277, 2006 WL 2828419 (D.Conn., Sept. 28, 2006). In this case, the Civil Service Board found itself in the unfortunate position of having no good alternatives. We are not unsympathetic to the plaintiffs’ expression of frustration. Mr. Ricci, for example, who is dyslexic, made intensive efforts that appear to have resulted in his scoring highly on one of the exams, only to have it invalidated. But it simply does not follow that he has a viable Title VII claim. To the contrary, because the Board, in refusing to validate the exams, was simply trying to fulfill its obligations under Title VII when confronted with test results that had a disproportionate racial impact, its actions were protected.

What Judge Sotomayor did not know was that the Supreme Court would use Ricci as a white person’s manifesto, holding that acts taken to combat discrimination should be suspected as acts “because of race,” that themselves must be justified by “strong evidence.” In practice, the Supreme Court actually applied the dubious and unachievable “enough evidence to leave Justices Scalia and Alito without any doubt” test.

In fact, the Ricci decision that Judge Sotomayor joined in affirming was unremarkable. The New Haven Fire Department, once virtually all white like many fire departments, has progressed by 2003 to 30% African-American and 16% Hispanic. However, the lieutenant and captain positions remained disproportionately white, with the senior officers 9% African American and 9% Hispanic. Only one of 21 captains was an African American. For reference, the overall population of New Haven was 40% African-American and 20% Hispanic.

Against this background, New Haven commissioned new tests for Fire Department lieutenant and captain. Apparently, the tests were multiple choice. It is unlikely that such memorization tests truly discern whether a person has what it takes to be a fire department officer, which has been described as “steady command presence, sound judgment and the ability to make life-or-death decisions under pressure.”

The results were racially disparate with African-Americans and Hispanics passing at a rate of half or less than Caucasians. Because promotions had to be made from the top three on each test, although there were qualified African-Americans and Hispanics from the testing, the 8 new lieutenants would all be white and two Hispanics and no African Americans would be eligible for the 8 captain positions.

This is a classic case of “disparate impact,” in which whites did disproportionately better than minorities. Intent is irrelevant given the result, and under established law, such a result can be justified only if the test can be shown to actually measure the characteristics needed to be a fire department officer. Ricci’s lawyers and the Supreme Court majority acknowledge this standard.

As a practical matter, previous tests in New Haven had resulted in somewhat more eligible minority candidates and different tests in nearby Bridgeport had resulted in minority firefighters holding one third of the lieutenant and captain positions. The question thus was whether the New Haven test measured job related qualifications or not.

The CSB held several hearings, listening to testimony from the company that developed the test, experts and others. If you read the trial court opinion and all of the Supreme Court opinions, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that there was enough evidence to support a decision to use the test and also, certainly, enough to support designing a new test.

The company that developed the test appears to have gone about it in a thoughtful way, but some questions were inappropriate and the 60% weighting of the written part of the test, based on the collective bargaining agreement with the white dominated union, was inherently questionable. Bridgeport for example, placed greater weight on the oral portion to reflect the real life conditions of firefighting and resulting in more even performance among ethnic groups.

Eventually, the CSB deadlocked 2-2, meaning that the test was not approved and a new one would be developed and held. This decision was upheld by Judge Sotomayor’s court as reasonably supported by the evidence.

Justice Ginzburg, speaking for three other Justices in her heartfelt Supreme Court dissent, goes over the hearings and the reasons given by the CSB members, one of whom was predisposed to approve the test, but ultimately changed his mind. She convincingly describes a thoughtful decision by a deliberative body that she, and Judge Sotomayor thought should be upheld.

Justice Kennedy and four others disagree. They characterize the decision to hold a new test as a race based action that must be justified by “strong” evidence. In their Sean Hannity world, attempts to ameliorate historic racism actually are discrimination themselves and civil service tests that mainly measure race and not qualifications are just a fact of life. Mr. Ricci, or at least some white people, since his performance on the test did not guarantee a promotion, somehow obtained a vested right to become fire department officers even though half of the CSB felt that the test could not be sufficiently related to job skills to justify the unquestioned discriminatory effect.

But wait, there’s more. Justice Alito, joined by Scalia and Thomas, blames the whole kafuffle on a black reverend who argued colorfully for the test to be thrown out and that for too long, the senior officers in the New Haven Fire Department had been white, and, perhaps, white Italian-Americans. These three strict constructionists assume and assert that the CSB knuckled under to this pressure. Apparently one does not need “strong evidence” to make these kinds of charges.

Although this sort of scared reasoning may appeal to white workers looking for a scapegoat for their lot in life, we expect more of Supreme Court Justices. Sean Hannity more or less held a victory parade for Frank Ricci and the “New Haven 20.” Pat Buchanan and George Will weighed in on behalf of white people.

Of course, Judge Sotomayor was right on this on as were the four dissenters on the Supreme Court. There was plenty of evidence to support the CSB decision to seek a test that would better measure job qualifications.

Right to a multiple choice test vindicated. AP Photo

But what about nice Mr. Ricci, the dyslexic Italian American lionized by Charles Krauthammer and others as the victim? Like Joe the Plumber, Ricci is not quite what he seems. As Dahlia Lithwick reported Friday, Ricci has made something of a career of being aggrieved. When he was not hired in 1995 by the New Haven Fire Department as a 20 year old (as 1 of 795 candidates seeking 40 jobs), he sued, claiming that the reason he was not among the elite was that he had mentioned his dyslexia during an interview.

The suit settled in December 2007 and Ricci received a job in the New Haven Fire Department and $11,000 in attorneys fees, This was a good thing for Ricci because he seems to have been fired by Middletown’s South Fire District in August 1997. The reasons were not disclosed, but Ricci charged it was because the union had appointed him to investigate safety conditions at a fire.

In 1998, Ricci challenged his Middletown dismissal and started a campaign asserting that the fire chief’ was not qualified for his position. The Connecticut Department of Labor Investigation ruled that Ricci’s firing was justified. Ricci vowed to challenge his termination in court, but it is unclear if he ever did so.

This was the start of Ricci against the world. The news articles quote Ricci extolling his own credentials. I am just relying on what is in the newspaper, but Ricci’s New Haven complaint filed on January 19, 1995 says he was twenty years old on that date and a Hartford Courant article on August 8, 1997 says he had 8 years firefighting experience in Maryland before joining the Middletown department “according to sources within the fire department.” Figuring like Columbo, this would mean that he joined the fire department during middle school. I end up pretty confused.

Ricci is such a hero that the Republicans are going to call him to testify. This is a delicate subject, as can be seen by the comments that Lithwick’s article has drawn, but Ricci has fought his fourteen year battle against discrimination in public, and it is only fair to examine whether he really is a victim, both as a matter of Constitutional law and personally. Or is he exactly the type of litigious individual that Republicans rail against. No problem there, but they may have trouble getting their story straight.

In fairness, the Hartford Courant reported in November 1998 that Ricci saved a woman’s life as a New Haven fire fighter. I do not question that he is a brave and skilled fire fighter. I question whether he has a lawsuit that should make him the white man’s hero.

But I digress, annoyed by Fox News and its ilk. The real question is whether Judge Sotomayor should be affirmed. As the above indicates, on Ricci, she is in line with four of the nine current members of the U.S. Supreme Court. It is not she who is starting a race war. Those who insist that actions may not take race into account, even to remedy situations where minorities are clearly disadvantaged, are the true activists, thwarting the Civil Rights Act and the Constitutional provisions on which it is based.